Minimizing Collateral Effects of Antibiotic Administration in Swine Farms: A Balancing Act

By Dr Merideth Parke BVSc, Regional Technical Manager Swine, EW Nutrition

We care for our animals, and antibiotics are a crucial component in the management of disease due to susceptible pathogens, supporting animal health and welfare. However, the administration of antibiotics in pig farming has become a common practice to prevent bacterial infections, reduce economic losses, and increase productivity.

All antibiotic applications have collateral consequences of significance, bringing a deeper consideration to their non-essential application. This article aims to challenge the choice to administer antibiotics by exploring the broader impact that antibiotics have on animal and human health, economies, and the environment.

Antibiotics disrupt microbial communities

Antibiotics do not specifically target pathogenic bacteria. By impacting beneficial microorganisms, they disrupt the natural balance of microbial communities within animals. They reduce the microbiota diversity and abundance of all susceptible bacteria – beneficial and pathogenic ones… many of which play crucial roles in digestion, brain function, the immune system, and respiratory and overall health. Resulting microbiota imbalances may present themselves in animals showing health performance changes associated with non-target systems, including the nasal, respiratory, or gut microbiome10, 9, 16. The gut-respiratory microbiome axis is well-established in mammals. Gut microbiota health, diversity, and nutrient supply directly impact respiratory health and function15. In pigs specifically, the modulation of the gut microbiome is being considered as an additional tool in the control of respiratory diseases such as PRRS due to the link between the digestion of nutrients, systemic immunity, and response to pulmonary infections12.

The collateral effect of antibiotic administration disrupting not only the microbial communities throughout the animal but also linked body systems needs to be considered significant in the context of optimal animal health, welfare, and productivity.

Antibiotic use can lead to the release of toxins

The consideration of the pathogenesis of individual bacteria is critical to mitigate potential for direct collateral effects associated with antibiotic administration. For example, in cases of toxin producing bacteria, when animals are medicated either orally or parenterally, mortality may increase due to the associated release of toxins when large numbers of toxin producing bacteria are killed quickly3.

Modulation of the brain function can be critical

Numerous animal studies have investigated the modulatory role of intestinal microbes on the gut-brain axis. One identified mechanism seen with antibiotic-induced changes in fecal microbiota is the decreased concentrations of hypothalamic neurotransmitter precursors, 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin), and dopamine6. Neurotransmitters are essential for communication between the nerve cells. Animals with oral antibiotic-induced microbiota depletion have been shown to experience changes in brain function, such as spatial memory deficits and depressive-like behaviors.

Processing of waste materials can be impacted

Anaerobic treatment technology is well accepted as a feasible management process for swine farm wastewater due to its relatively low cost with the benefit of bioenergy production. Additionally, the much smaller volume of sludge remaining after anaerobic processing further eases the safe disposal and decreases the risk associated with the disposal of swine waste containing residual antibiotics5.

The excretion of antibiotics in animal waste, and the resulting presence of antibiotics in wastewater, can impact the success of anaerobic treatment technologies, which already could be demonstrated by several studies8, 13. The degree to which antibiotics affect this process will vary by type, combination, and concentration. Furthermore, the presence of antibiotics within the anaerobic system may result in a population shift towards less sensitive microbes or the development of strains with antibiotic-resistant genes1, 14.

Antibiotics can be transferred to the human food chain

Regulatory authorities specify detailed withdrawal periods after antibiotic treatment. However, residues of antibiotics and their metabolites may persist in animal tissues, such as meat and milk, even after this period. These residues can enter the human food chain if not adequately monitored and controlled.

Prolonged exposure to low levels of antibiotics through the consumption of animal products may contribute to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in humans, posing a significant public health risk.

Contamination of the environment

As already mentioned before, the administration of antibiotics to livestock can result in the release of these compounds into the environment. Antibiotics can enter the soil, waterways, and surrounding ecosystems through excretions from treated animals, inappropriate disposal of manure, and runoff from agricultural fields. Once in the environment, antibiotics can contribute to the selection and spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in natural bacterial communities. This contamination poses a potential risk to wildlife, including birds, fish, and other aquatic organisms, as well as the broader ecological balance of affected ecosystems.

Every use of antibiotics can create resistance

One of the widely researched concerns associated with antibiotic use in livestock is the development of antibiotic resistance. The development of AMR does not require prolonged antibiotic use and, along with other collateral effects, also occurs when antibiotics are used within recommended therapeutic or preventive applications.

Gene mutations can supply bacteria with abilities that make them resistant to certain antibiotics (e.g., a mechanism to destroy or discharge the antibiotic). This resistance can be transferred to other microorganisms, as seen with the effect of carbadox on Escherichia coli7 and Salmonella enterica2 and the carbadox and metronidazole effect on Brachyspira hyodysenteriae16. Additionally, there is an indication that the zinc resistance of Staphylococcus of animal origin is associated with the methicillin resistance coming from humans4.

Consequently, the effectiveness of antibiotics in treating infections in target animals becomes compromised, and the risk of exposure to resistant pathogens for in-contact animals and across species increases, including humans.

Alternative solutions are available

To successfully minimize the collateral effects of antibiotic administration in livestock, a unified strategy with support from all stakeholders in the production system is essential. The European Innovation Partnership – Agriculture11 concisely summarizes such a process as requiring…

- Changing human mindsets and habits: this is the first and defining step to successful antimicrobial reduction

- Improving pig health and welfare: Prevention of disease with optimal husbandry, hygiene, biosecurity, vaccination programs, and nutritional support.

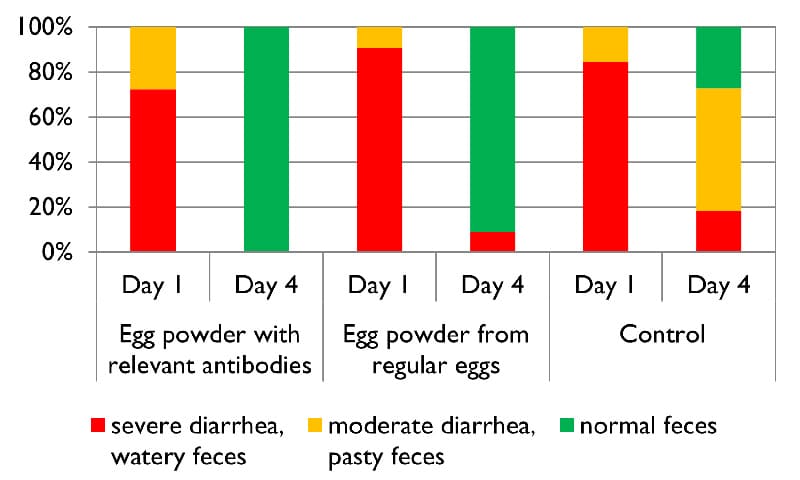

- Effective antibiotic alternatives: for this purpose, phytomolecules, pro/pre-biotics, organic acids, and immunoglobulins are considerations.

In general, implementing responsible antibiotic stewardship practices is paramount. This includes limiting antibiotic use to the treatment of diagnosed infections with an effective antibiotic, and eliminating their use as growth promotors or for prophylactic purposes.

Keeping the balance is of crucial importance

While antibiotics play a crucial role in ensuring the health and welfare of livestock, their extensive administration in the agricultural industry has collateral effects that cannot be ignored. The development of antibiotic resistance, environmental contamination, disruption of microbial communities, and the potential transfer of antibiotic residues to food pose significant challenges.

Adopting responsible antibiotic stewardship practices, including veterinary oversight, disease prevention programs, optimal animal husbandry practices, and alternatives to antibiotics, can strike a balance between animal health, efficient productive performance, and environmental and human health concerns.

The collaboration of stakeholders, including farmers, veterinarians, policymakers, industry and consumers, is essential in implementing and supporting these measures to create a sustainable and resilient livestock industry.

References

- Angenent, Largus T., Margit Mau, Usha George, James A. Zahn, and Lutgarde Raskin. “Effect of the Presence of the Antimicrobial Tylosin in Swine Waste on Anaerobic Treatment.” Water Research 42, no. 10–11 (2008): 2377–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2008.01.005.

- Bearson, Bradley L., Heather K. Allen, Brian W. Brunelle, In Soo Lee, Sherwood R. Casjens, and Thaddeus B. Stanton. “The Agricultural Antibiotic Carbadox Induces Phage-Mediated Gene Transfer in Salmonella.” Frontiers in Microbiology 5 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00052.

- Castillofollow, Manuel Toledo, Rocío García Espejofollow, Alejandro Martínez Molinafollow, María Elena Goyena Salgadofollow, José Manuel Pintofollow, Ángela Gallardo Marínfollow, M. Toledo, et al. “Clinical Case: Edema Disease – the More I Medicate, the More Pigs Die!” $this->url_servidor, October 15, 2021. https://www.pig333.com/articles/edema-disease-the-more-i-medicate-the-more-pigs-die_17660/.

- Cavaco, Lina M., Henrik Hasman, Frank M. Aarestrup, Members of MRSA-CG:, Jaap A. Wagenaar, Haitske Graveland, Kees Veldman, et al. “Zinc Resistance of Staphylococcus Aureus of Animal Origin Is Strongly Associated with Methicillin Resistance.” Veterinary Microbiology 150, no. 3–4 (2011): 344–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.02.014.

- Cheng, D.L., H.H. Ngo, W.S. Guo, S.W. Chang, D.D. Nguyen, S. Mathava Kumar, B. Du, Q. Wei, and D. Wei. “Problematic Effects of Antibiotics on Anaerobic Treatment of Swine Wastewater.” Bioresource Technology 263 (2018): 642–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2018.05.010.

- Köhler, Bernd, Helge Karch, and Herbert Schmidt. “Antibacterials That Are Used as Growth Promoters in Animal Husbandry Can Affect the Release of Shiga-Toxin-2-Converting Bacteriophages and Shiga Toxin 2 from Escherichia Coli Strains.” Microbiology 146, no. 5 (2000): 1085–90. https://doi.org/10.1099/00221287-146-5-1085.

- Loftin, Keith A., Cynthia Henny, Craig D. Adams, Rao Surampali, and Melanie R. Mormile. “Inhibition of Microbial Metabolism in Anaerobic Lagoons by Selected Sulfonamides, Tetracyclines, Lincomycin, and Tylosin Tartrate.” Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 24, no. 4 (2005): 782–88. https://doi.org/10.1897/04-093r.1.

- Looft, Torey, Heather K Allen, Brandi L Cantarel, Uri Y Levine, Darrell O Bayles, David P Alt, Bernard Henrissat, and Thaddeus B Stanton. “Bacteria, Phages and Pigs: The Effects of in-Feed Antibiotics on the Microbiome at Different Gut Locations.” The ISME Journal 8, no. 8 (2014a): 1566–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.12.

- Looft, Torey, Heather K. Allen, Thomas A. Casey, David P. Alt, and Thaddeus B. Stanton. “Carbadox Has Both Temporary and Lasting Effects on the Swine Gut Microbiota.” Frontiers in Microbiology 5 (2014b). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00276.

- Nasralla, Meisoon. “EIP-Agri Concept.” EIP-AGRI – European Commission, September 11, 2017. https://ec.europa.eu/eip/agriculture/en/eip-agri-concept.html.

- Niederwerder, Megan C. “Role of the Microbiome in Swine Respiratory Disease.” Veterinary Microbiology 209 (2017): 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.02.017.

- Poels, J., P. Van Assche, and W. Verstraete. “Effects of Disinfectants and Antibiotics on the Anaerobic Digestion of Piggery Waste.” Agricultural Wastes 9, no. 4 (1984): 239–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0141-4607(84)90083-0.

- Shimada, Toshio, Julie L. Zilles, Eberhard Morgenroth, and Lutgarde Raskin. “Inhibitory Effects of the Macrolide Antimicrobial Tylosin on Anaerobic Treatment.” Biotechnology and Bioengineering 101, no. 1 (2008): 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.21864.

- Sikder, Md. Al, Ridwan B. Rashid, Tufael Ahmed, Ismail Sebina, Daniel R. Howard, Md. Ashik Ullah, Muhammed Mahfuzur Rahman, et al. “Maternal Diet Modulates the Infant Microbiome and Intestinal Flt3l Necessary for Dendritic Cell Development and Immunity to Respiratory Infection.” Immunity 56, no. 5 (May 9, 2023): 1098–1114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2023.03.002.

- Slifierz, Mackenzie Jonathan. “The Effects of Zinc Therapy on the Co-Selection of Methicillin-Resistance in Livestock-Associated Staphylococcus Aureus and the Bacterial Ecology of the Porcine Microbiota,” 2016.

- Stanton, Thaddeus B., Samuel B. Humphrey, Vijay K. Sharma, and Richard L. Zuerner. “Collateral Effects of Antibiotics: Carbadox and Metronidazole Induce VSH-1 and Facilitate Gene Transfer among Brachyspira Hyodysenteriae” Applied and Environmental Microbiology 74, no. 10 (2008): 2950–56. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.00189-08.