Mitigating Eimeria resistance in broiler production with phytogenic solutions

By Dr. Ajay Bhoyar, Global Technical Manager, EW Nutrition

In modern, intensive poultry production, the imminent threat of resistant Eimeria looms large, posing a significant challenge to the sustainability of broiler operations. Eimeria spp., capable of developing resistance to our traditional interventions, has emerged as a pressing global issue for poultry operators. The resistance of Eimeria to conventional drugs, coupled with concerns over drug residue, has necessitated a shift towards natural, safe, and effective alternatives.

Several phytogenic compounds, including saponins, tannins, essential oils, flavonoids, alkaloids, and lectins, have been the subject of rigorous study for their anticoccidial properties. Among these, saponins and tannins in specific plants have emerged as powerful tools in the fight against these resilient protozoa. In the following, we delve into innovative strategies that leverage the potential of these compounds, particularly saponins and tannins, to prevent losses by mitigating the risk of resistant Eimeria in poultry production.

Understanding resistant Eimeria in broiler production

The World Health Organization Scientific Group (World Health Organization, 1965) developed the definition of resistance in broad terms as ‘the ability of a parasite strain to survive and/or to multiply despite the administration and absorption of a drug given in doses equal to or higher than those usually recommended but within the limits of tolerance of the subject’.

The high reproduction rate of Eimeria spp. allows them to evolve quickly and develop resistance to drugs used for their control. Moreover, the resistant strains of Eimeria can persist in the environment due to their ability to form resistant oocysts, leading to the re-infection of animals and further spread of resistant strains.

Resistant Eimeria strains present many challenges in modern poultry farming, significantly impacting overall productivity and economic sustainability. However, one of the primary challenges is the reduced efficacy of traditional anti-coccidial drugs.

Eimeria resistance occurs in different types

There are different possibilities as to why Eimeria are resistant to specific drugs.

Acquired resistance results from heritable decreases in the sensitivity of specific strains and species of Eimeria to drugs over time. There are two types of acquired resistance: partial and complete. These types depend upon the extent of sensitivity lost. There is a direct relationship between the concentration of the drug and the degree of resistance. A strain controlled by one drug dose may show resistance when a lower concentration of the same drug is administered.

Cross-resistance is the sharing of resistance among different compounds with similar modes of action (Abbas et al., 2011). This, however, may not always occur (Chapman, 1997).

Multiple resistance is resistance to more than one drug, even though they have different modes of action (Chapman, 1993).

Natural substances can bring back the efficacy of anticoccidial measures

It was found that if a drug to which the parasite has developed resistance is withdrawn from use for some time or combined with another effective drug, the sensitivity to that drug may return (Chapman, 1997).

Botanicals and natural identical compounds are well renowned for their antimicrobial and antiparasitic activity, so they can represent a valuable tool against Eimeria (Cobaxin-Cardenas, 2018). The mechanisms of action of these molecules include degradation of the cell wall, cytoplasm damage, ion loss with reduction of proton motive force, and induction of oxidative stress, which leads to inhibition of invasion and impairment of Eimeria spp. development (Abbas et al., 2012; Nazzaro et al., 2013). Natural anticoccidial products may provide a novel approach to controlling coccidiosis while meeting the urgent need for control due to the increasing emergence of drug-resistant parasite strains in commercial poultry production (Allen and Fetterer, 2002).

Saponins and Tannins: Nature’s Defense against Eimeria Challenge

Phytogenic solutions, specifically those based on saponins and tannins, have recently surfaced as promising alternatives to mitigate the Eimeria challenge in poultry production. By harnessing the power of these natural compounds, poultry producers can boost the resilience of their flocks against the Eimeria challenge, promoting both the birds’ welfare and the industry’s sustainability.

Saponins are glycosides found in many plants with distinctive soapy characteristics due to their ability to foam in water. In the context of Eimeria, saponins can disrupt the integrity of the parasites’ cell membranes. When consumed, saponins can interfere with the protective outer layer of Eimeria, weakening the parasite and rendering it vulnerable to the host’s immune responses. This disruption impedes the ability of Eimeria to attach to the intestinal lining and reproduce, effectively curtailing the infection.

Tannins are polyphenolic compounds with astringent properties, occurring in various plant parts, such as leaves, bark, and fruits. Choosing the proper tannin at the right level and time is crucial to realize the benefits of tannin-based feed additives.

In the context of Eimeria, tannins exhibit several mechanisms of action. Firstly, they bind to proteins within the parasites, disrupting their enzymatic activities and metabolic processes. This interference weakens Eimeria, hindering its ability to cause extensive damage to the intestinal lining. Secondly, tannins are anti-inflammatory, reducing the inflammation caused by Eimeria infections. Additionally, tannins act as antioxidants, protecting the intestinal cells from oxidative stress induced by the parasite.

When incorporated into broilers’ diets, saponins and tannins create an unfavorable environment for Eimeria, inhibiting their growth and propagation within the host. Moreover, these compounds fortify the broiler’s natural defenses, enhancing its ability to resist Eimeria infections. By leveraging the innate properties of saponins and tannins, the impact of resistant Eimeria strains can effectively be managed and mitigated, fostering healthier flocks and sustainable poultry production.

What is Pretect D?

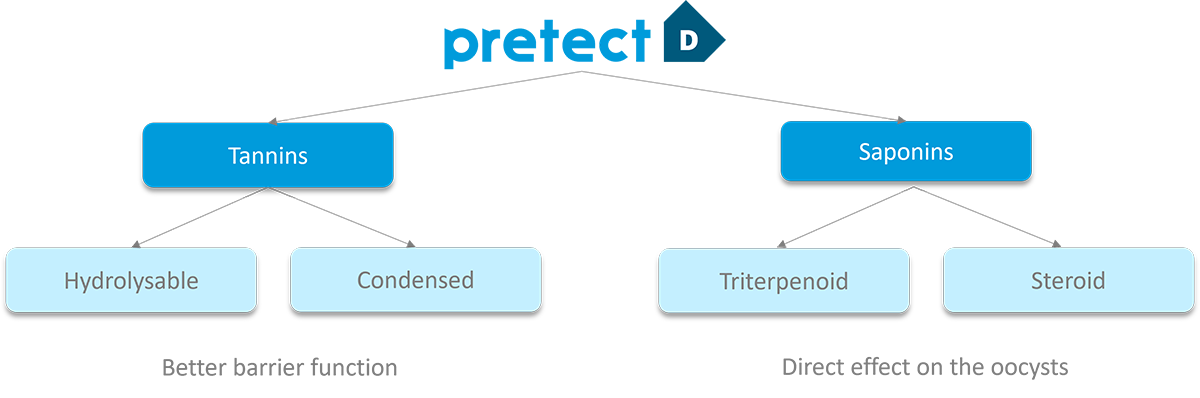

Pretect D is a unique proprietary blend of phytomolecules, including saponins and tannins, that supports the control of coccidiosis challenges in poultry production. It can be used alone or in combination with coccidiosis vaccines, ionophores, and chemicals as part of a shuttle or rotation program.

Fig.1. Key active ingredients of Pretect D

Fig.1. Key active ingredients of Pretect D

Modes of action of Pretect D

Pretect D exhibits multiple modes of action to optimize gut health during challenging times. Due to its anti-protozoal, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antioxidant properties, it

- effectively decreases oocyst excretion and disease spread

- promotes restoring the mucosal barrier function and improves intestinal morphology

- protects the intestinal epithelium from inflammatory and oxidative damage.

The beneficial effects of Pretect D

The beneficial effects of Pretect D’s inclusion in the coccidiosis control program include improving overall gut health and broiler production performance.

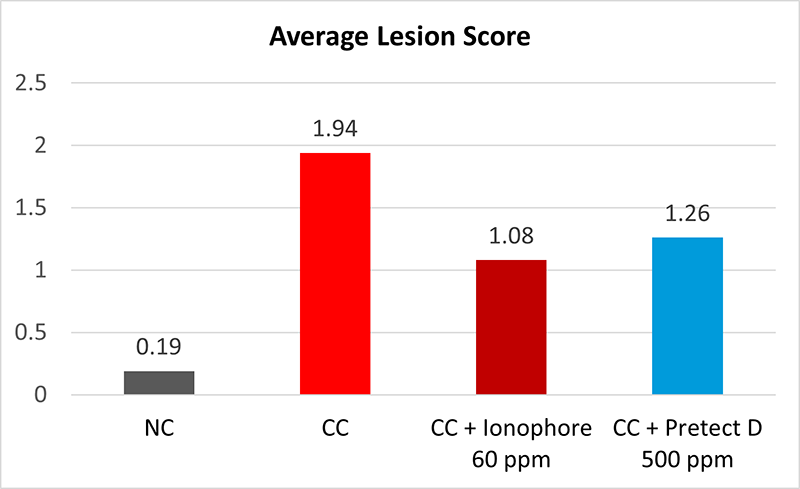

In a challenge study with Cobb 500 broiler chicks under a mixed Eimeria inoculum challenge, it was evident that the group receiving Pretect D (@500g/ton) in the feed throughout the 35-day rearing period had less coccidia-caused lesions (D27) than the broilers challenged and fed control diets.

Fig. 2: Pretect D reduced coccidia-caused lesions in broilers

Fig. 2: Pretect D reduced coccidia-caused lesions in broilers

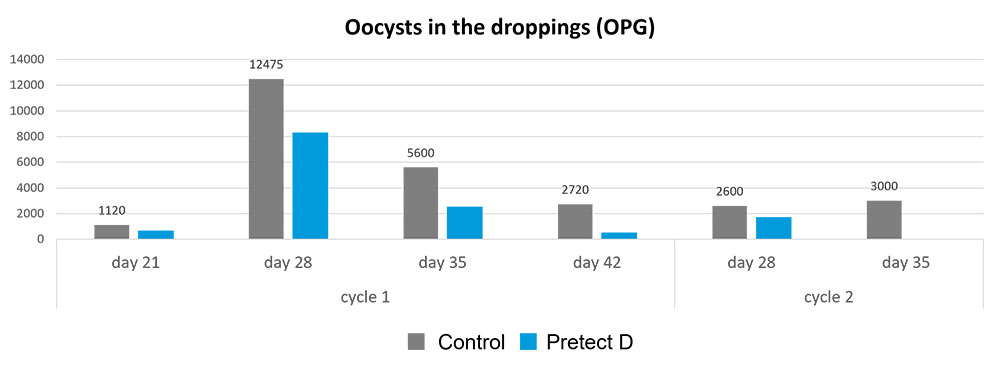

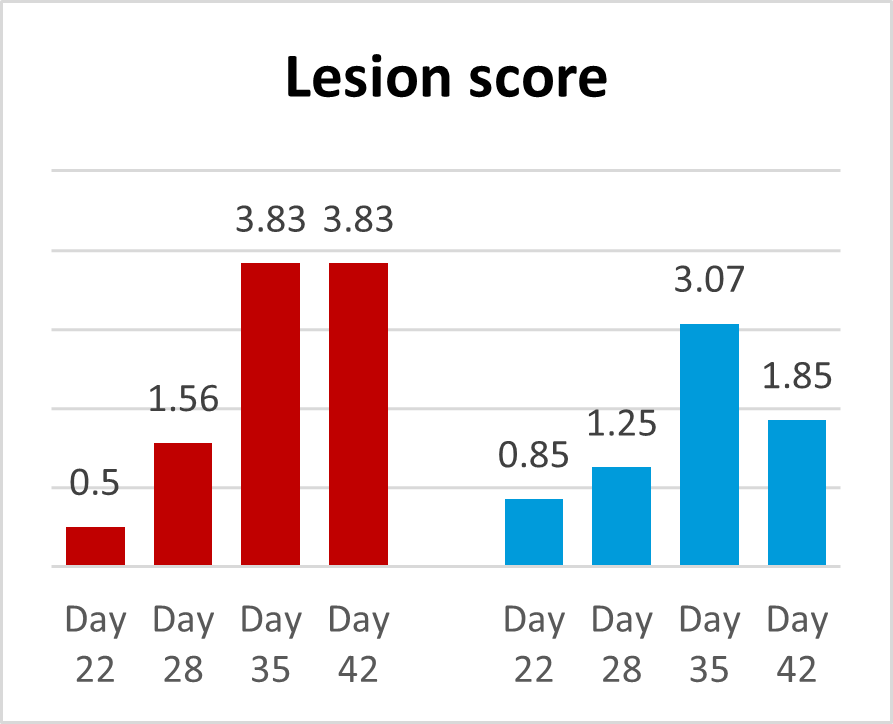

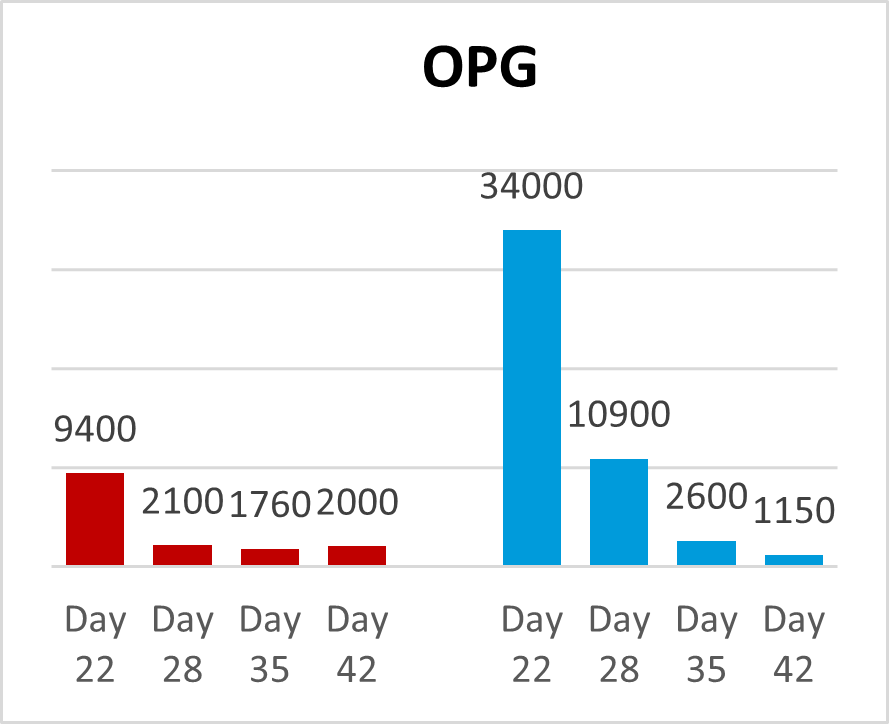

In another field study, a traditional anticoccidial program (Starter and Grower I feeds: Narasin + Nicarbazin, Grower II feed: Salinomycin, Finisher/ withdrawal feeds: No anticoccidial) was compared with a program combining anticoccidials with Pretect D (Starter and Grower I feeds: Narasin + Nicarbazin, Grower II and Finisher feeds: Pretect D). The addition of Pretect D significantly reduced OPG count and lowered the coccidiosis lesion score compared to the control (Fig. 3).

![]()

Fig.3. Pretect D reduced broilers’ coccidiosis lesion score and OPG count

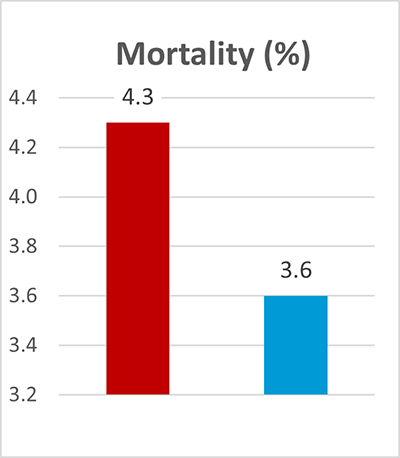

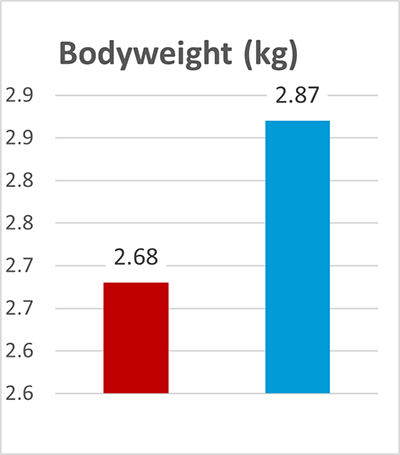

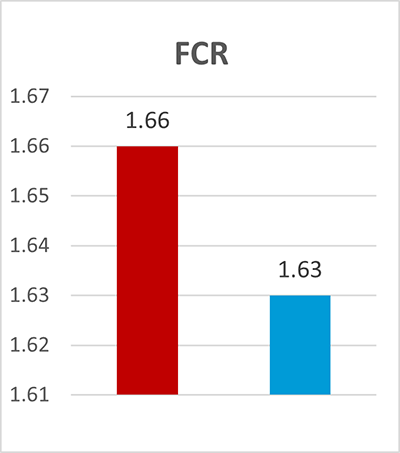

Consequently, broilers receiving Pretect D showed better overall production performance.

![]()

Fig. 4. Overall improved production performance by Pretect D

Pretect D: Application Strategies

The introduction of an effective phytogenic combination in the coccidiosis control program can help mitigate the drug resistance issue. Such a natural anticoccidial solution can be used as a standalone, preferably in less challenging months, as well as in combination with chemicals (shuttle/ rotation) or a coccidiosis vaccine (bio-shuttle), reducing the need for frequent drug use.

Shuttle programs are commonly employed for managing coccidiosis, and they yield a satisfactory level of success. Within these programs, multiple drugs from distinct classes of anticoccidials are administered throughout a single flock. For instance, one class of drug is utilized in the starter feed, another in the grower stage, reverting to the initial class for the finisher diet and concluding with a withdrawal period.

In rotation programs, anticoccidial drugs are alternated between batches rather than within a single batch.

Conclusions

Coccidiosis is considered one of the most economically significant diseases of poultry and the development of anticoccidial resistance has threatened the profitability of the broiler industry. Therefore, regularly monitoring Eimeria species to develop resistance against different anticoccidial groups is crucial to managing resistance and choosing an anticoccidial. It would be rewarding to use an effective phytogenic solution in the coccidiosis control program as a strategic and tactical measure and to focus on such integrated programs for drug resistance management in the future.

References:

Abbas, R.Z., D.D. Colwell, and J. Gilleard. “Botanicals: An Alternative Approach for the Control of Avian Coccidiosis.” World’s Poultry Science Journal 68, no. 2 (June 1, 2012): 203–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0043933912000268.

Abbas, R.Z., Z. Iqbal, D. Blake, M.N. Khan, and M.K. Saleemi. “Anticoccidial Drug Resistance in Fowl Coccidia: The State of Play Revisited.” World’s Poultry Science Journal 67, no. 2 (June 1, 2011): 337–50. https://doi.org/10.1017/s004393391100033x.

Allen, P. C., and R. H. Fetterer. “Recent Advances in Biology and Immunobiology ofEimeriaSpecies and in Diagnosis and Control of Infection with These Coccidian Parasites of Poultry.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 15, no. 1 (January 2002): 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.15.1.58-65.2002.

Chapman, H. D. “Biochemical, Genetic and Applied Aspects of Drug Resistance inEimeriaParasites of the Fowl.” Avian Pathology 26, no. 2 (June 1997): 221–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079459708419208.

Chapman, H.D. “Resistance to Anticoccidial Drugs in Fowl.” Parasitology Today 9, no. 5 (May 1993): 159–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-4758(93)90137-5.

Cobaxin-Cárdenas, Mayra E. “Natural Compounds as an Alternative to Control Farm Diseases: Avian Coccidiosis.” Farm Animals Diseases, Recent Omic Trends and New Strategies of Treatment, March 21, 2018. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.72638.

Nazzaro, Filomena, Florinda Fratianni, Laura De Martino, Raffaele Coppola, and Vincenzo De Feo. “Effect of Essential Oils on Pathogenic Bacteria.” Pharmaceuticals 6, no. 12 (November 25, 2013): 1451–74. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph6121451.

Pop, Loredana Maria, Erzsébet Varga, Mircea Coroian, Maria E. Nedișan, Viorica Mircean, Mirabela Oana Dumitrache, Lénárd Farczádi, et al. “Efficacy of a Commercial Herbal Formula in Chicken Experimental Coccidiosis.” Parasites & Vectors 12, no. 1 (July 12, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3595-4.

World Health Organization Technical Report Series No. 296, (1965) pp:. 29.